The Story

The San Francisco Bay is the largest landlocked harbor in the world, covering more than 400 square miles. Few locals realize that there are only four deep water ports in the San Francisco Bay–Redwood City, San Francisco, Oakland and Stockton. Redwood City is historically quite important to the nautical past of the Bay and in the mid-1800’s was a thriving seaport, jammed with sailing ships loading and unloading cargo, especially logs and cut wood. The “Redwood Embarcadero” was the main wharf located at what is now Main and Broadway in downtown Redwood City, and it was the town’s center of activity. In the past Redwood City boasted twelve shipyards producing wooden sailing ships of substantial size. The first was the schooner “Redwood” built by G.M. Burnham in 1851, the same year the first house in Redwood City was erected by Captain A. Smith. “Redwood” was followed by a series of schooners (including the “Mary Martin”, “Caroline Whipple”, “Harriett” and the “Dashaway”), and the last was “Perseverence” launched in 1883. Today the original compass from the “Redwood” is displayed in the Westpoint Harbor office.

Early days excavating the marina basin at Westpoint Harbor using “long-reach” excavators on wood mats

In the 19th century all the action was in the coastal mountains, with little development on the Bay except Redwood City. Lumber and shingles were milled and hauled by wagon to the wharves and crews working in the mountains all week came to Redwood City to carouse on the weekends before returning to the mills on Monday–it was bars, boats and brothels. Shipyards were located along Redwood Creek and its two arms (Westpoint Slough being the largest) together with wharves for loading and unloading goods.

With its rich and interesting maritime history, it is fitting that Redwood City’s Westpoint Slough is the site of a world-class marina and boatyard facility. But it’s not the first time: The Westpoint Harbor site was once home to the Portland Shipbuilding Company which built concrete ships in the late 1800’s to about 1918, using cement produced nearby. (Cement was produced using oyster shells and Bay mud on what is now Pacific Shores Center, the only facility in California to make cement in this manner).

Concrete manufacturing using Bay mud and oyster shells.

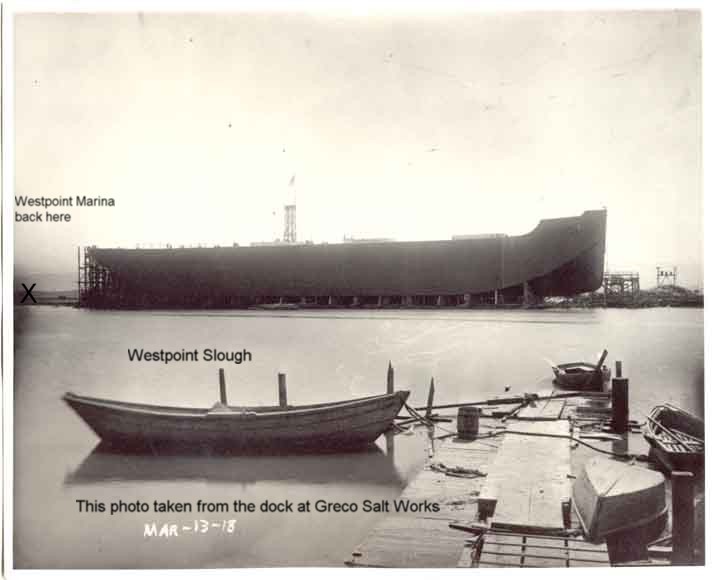

Concrete shipbuilding on Westpoint Slough on site of Westpoint Harbor

Concrete ship Faith as viewed from Greco Island

The most famous of the concrete ships was the “Faith”.

The boat yard area later became a “bittern pond” used by the Leslie Salt Company. Bittern is a byproduct of saltmaking and was used to produce magnesia and other products for plants in Redwood City and San Francisco. Never a salt pond, the site was zoned “heavy industrial” reflecting its history as a shipyard and chemical storage until its purchase from Leslie Salt to create Westpoint Harbor.

Compatibility

The Westpoint Harbor project plan for a full service marina consists of 416-berths and attendant boatyard and marine services. Also included are restaurants, yacht club, rowing center, fuel dock and other maritime businesses consistent with a marina resort. The harbor features 1000 feet of transient/guest docks and a passenger loading and unloading dock too.

This area is zoned “tidal plain” which specifically supports marina and boatyard activities, and Westpoint Harbor is consistent with the stated public desire to maintain this area as a recreational maritime region. It’s in the Port of Redwood City’s “sphere of influence” and consistent with the “San Francisco Bay Area Seaport Plan” as prepared by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). In all, thirteen agencies were required to approve Westpoint Harbor, and all were unanimous ‘yes’ votes, creating the first new private marina in the Bay in decades.

Nearby activities include Cargill’s salt-farming operations to the south, the Pacific Shores Center office park to the west, and the Greco Island Wildlife Refuge to the north and east.

This project is compatible with Cargill salt activities. The adjacent land area is the remaining half of the “bittern pond,” and the Harbor provides a buffer between Westpoint Slough and Cargill’s ponds, especially the weather-exposed northern boundary. The Greco Island Wildlife Refuge is across Westpoint Slough from the harbor, and the marina affords viewing of Greco Island without directly affecting this sensitive site. Moreover, by supporting boating in the area the harbor allows close observation from the water without damage from direct access.

To the east is the Pacific Shores Center development. On first examination it may appear that the projects are neither compatible nor incompatible with little interaction except lunchtime visitors to the marina restaurants. On closer examination however, it is clear the projects are complimentary in many ways. Pacific Shores Center experiences high traffic periods on the somewhat constrained Seaport Boulevard, whereas Westpoint Harbor has light traffic which is mostly in the evening and weekends, so the two are not additive. Moreover, a reciprocal parking agreement means parking can be shared because there is little overlap. And finally Westpoint Harbor is a visual feature valued by Pacific Shores, adding to the mutually beneficial relationship.

The Port is Redwood City’s most valuable asset, and this project extends the port area to its logical conclusion at land’s end along Redwood City Creek and around Westpoint Slough. As a big-boat harbor, the marina adds measurably to the maritime nature of the city, and will provide the only marine fuel and boatyard facilities in the greater South Bay.

Finally, Westpoint Harbor provides water access to the Redwood Creek shipping channel via Westpoint Slough. A naturally deep channel, Westpoint Slough does not require periodic dredging as is often associated with marinas, and is thought to be the only practical (physical and economic) site south of the San Mateo bridge for a marina.

Environment

What about Bay wetlands? First of all, many people think most of the Bay’s historic tidal wetlands lay buried underneath freeways and high-rise buildings. Eighty percent lost? Ninety percent lost? The good news is the facts are vastly different. A technical report on San Francisco Bay wetlands (by Zenter and Zenter, a wetlands planning and restoration consulting firm) shows that only about 18% of San Francisco Bay has been lost as a result of urban use.

In 1850 (the earliest good records) there were about 195,000 acres of historic tidal marsh in and around San Francisco Bay. Today, 134,000 remain as wetlands (about 70%): 35,000 acres are tidal marsh, 35,000 more acres are salt ponds, 60,000 acres are non-tidal marsh and about 4,000 acres are wetlands within farmlands. Farming takes up another 23,000 acres, and the last 36,000 has indeed gone over to urban use.

From 1961 to 1981, an additional 717 acres have been allowed to be filled within historic wetlands. This is a half percent (0.5%). Towards the end of this period it was about six acres per year. And the situation actually gets better; This was “mitigated” by the restoration of over 6,000 acres, and the creation of 330 acres of new wetlands.

These days, conversion to urban use requires developers to create or convert about twice as much as is lost, so wetlands are now growing in the Bay. Cargill Salt Company sold the majority of its salt ponds to the state several years ago…the largest addition west of the Rocky Mountains. Add to this several large grants from Cargill over the years, and the picture is pretty good. All in all, we’ve done a good job of protecting our wetlands and offsetting losses in the last half-century, and the Bay is getting cleaner every year.

What about those Salt Ponds? Native Americans harvested salt along the Bay long before the 1849 gold rush. The first commercial salt activity started in 1856, and over the next 150 years nearly 100 salt-making outfits were consolidated into Leslie Salt, which was subsequently bought by Cargill. The first salt farming in Redwood City did not begin until the early 1900’s. Today about a million tons of salt per year come from solar evaporation of seawater along the Bay, using over 35,000 acres of ponds. This “salt farming” is a five-year cycle and involves concentrating, crystallizing and harvesting the salt which moves from pond to pond. You may have noticed the multi-colored ponds as you fly in to SFO which is due to the various organisms which thrive in different levels of salinity. After the salt is harvested, the residual material (bittern) is pumped into special chemical storage ponds.

- Wind-powered Archimedes pumps moving water between ponds at Leslie Salt

- Salt harvester scraping salt and loading into salt cars

- Salt cars on portable narrow-gauge railroad tracks

In Leslie’s Redwood City salt works “Pond 10″ was a bittern pond. Located at the end of a series of concentrator/crystalizer ponds used for salt-making, it borders Westpoint Slough at the end of the Seaport Boulevard. Because of the concentration of chemicals, bittern ponds are sterile and do not support life, and this chemical soup can be in crystal form and concentrated liquids on the surface, and in the summer it may be completely dry. As such, a bittern pond provides few wetland functions and represents something of an environmental liability.

As part of the Westpoint Harbor project all of the bittern was removed from Pond 10, and after four years of excavation the harbor basin was opened, adding 26.6 acres of new Bay surface. The flushing action of millions of gallons of additional water in and out the marina basin has helped rejuvenate Westpoint Slough.

First boats in Westpoint Harbor New Year’s Eve, 2006 after the basin was opened to the Bay

Climate

Few people realize the Bay surface controls our local climate on the San Francisco Peninsula… it’s the reason San Francisco can be 60 degrees, Redwood City can be 75, and San Jose can be 90! San Francisco and the central California coast are largely influenced by the cold current that comes down from Alaska, bringing our coastal fog and cool coastal weather. But the Bay is shallow and dark and absorbs sunlight and creates the warmth we enjoy in the Bay area. (This warm air rises, drawing cool air over the coastal mountains, and gives us the characteristic fog that looms over the hills like a blanket on summer days).

Westpoint Harbor was conceived as an “inland” project. It does not encroach in to the Bay and its navigable waters and there were no dredged materials to get hauled out and dumped. The site was planned so the 26 acre basin produced just enough material for the uplands portion of the marina. This is not the most efficient method from a developer’s perspective, but it is the most environmentally thoughtful. Westpoint Harbor is thought to be the largest private contribution to increasing the Bay’s surface area.

Finally, Westpoint Marina is near Greco Island, a wonderful wildlife refuge sheltering an array of wildlife, including several endangered species. One of the facets of Westpoint Harbor is the extension of the Bay Trail with viewing areas, and benches so people can see, but not tread on to Greco Island.

This is why the Friends of Redwood City, the California Boaters Association, Marina Recreation Association, Recreational Boaters of California, Audubon Society, the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Port and City of Redwood City have been supportive of Westpoint Harbor. Although it took twelve years to assemble all the permits required, there was no opposition to the project.